Television for children has characters that are children, right? It seems like an obvious assumption. The most clear way to communicate to a viewer that a show is for children, besides using puppets or animation, is to have the characters on the screen be the same age as the target audience. How does this relate to fairy tales?

Fairy tales have a tendency to be loosely structured and contain few details by way of location, age, or other characteristics. The most prevalent fairy tale plots can be summed up in three sentences, with the rest of the details left for adapters to fill in for themselves. This is why fairy tales have maintained their cultural relevance, and it also complicates the relationship between television, children as target audience, and fairy tales.

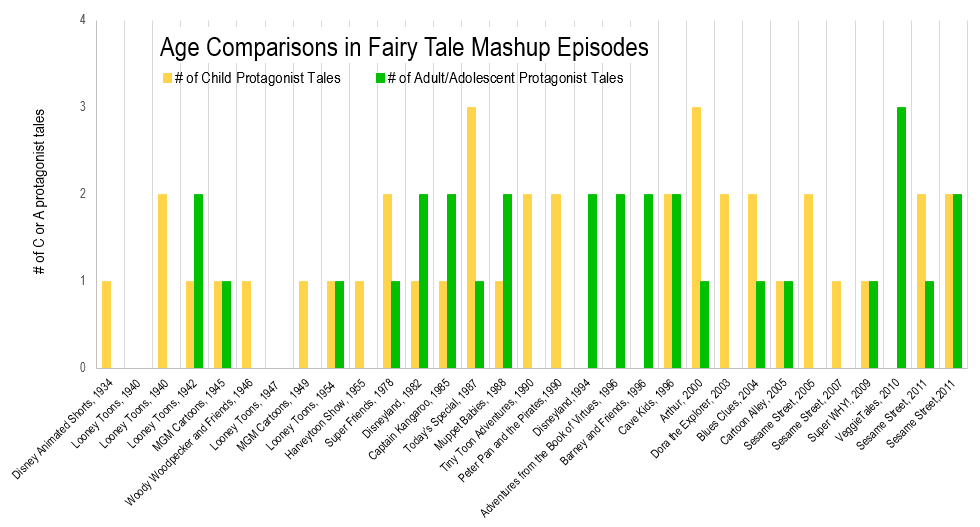

For my fairy tale mashup episode project, I attempted to follow the same pattern I did with the gender research, and hope that something equally as interesting came out of it. I categorized the tales between child protagonists and adults/adolescents protagonists. The tales resisted this. How old is Little Red Riding Hood is if few versions of the story specify?

Kay Stone, a storyteller and folklorist, came to my rescue in her book Someday Your Witch Will Come, in which she claims that it is at the onset of puberty “that Rapunzel is locked in a tower, Snow White is sent out to be murdered, and Sleeping Beauty is put to sleep.” I used this as the division between the tales I marked as ‘child’ and the tales with love narratives that I marked as ‘adolescent/adult.’

This graph resulted. It’s not as interesting as the gender patterns graph, and unlike the patterns that are evident in the pink and blue gender graph, the data resisted patterns or trends.

Analysis:

Do episodes pick one category or do they more often mix?

There are 14 episodes that use only adult characters or only child character tales. There are 15 episodes that take tales from both categories and mix them up.

Noticeably even and resisting a hypothesis either way.

So, what about those that use both adolescent tales and child characters? Is one group consistently more dominant? It would be expected that there would be more child tales in children’s television but…

5 where the children outnumber the adult/adolescents,

4 where the adults/adolescents outnumber the children

and,

6 where they are even.

These visualizations can be helpful in many cases, and I always strive to make them helpful as possible, but sometimes they end up illustrating the utter lack of patterns in the data and show it resisting conclusions no matter what kind of graph or axis I use.

But just because the data resists the creation of patterns doesn’t mean that there is nothing to learn from the way children’s television uses children and adults in fairy tales.

Since these fairy tale mashup episodes are most often single episodes that break from the norm of the show, the episodes use strategies that removes the tale from the normal narrative, either a storybook or a dream sequence.

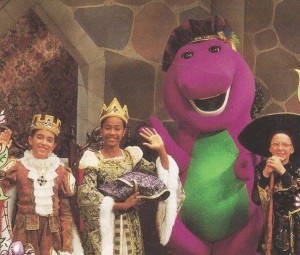

For example, in Barney’s Once Upon a Time, the children are instructed to use their imaginations while a storyteller is telling them the story of Rumpelstiltskin (ATU 500), which then visually transitions into the child actors playing the roles of the King, the Miller’s Daughter, and Rumpelstiltskin. This level of separation allows the tale with clearly adult characters to connect to the established child actors and audience members of Barney & Friends.

Another factor is the load of mashing up several fairy tales in the short form of the children’s TV show means that there is only a few minutes devoted to each tale motif. In the Arthur episode “Just Desserts” the Snow White (ATU 709) section of the episode is contained in one ‘dwarf’ introducing his six companions and the dwarves carrying DW/Snow White away to clean and cook for them. The explicit reference to Snow White makes the presence of the fairy tale clear, and there’s no time or plot reason to take the Snow White motif through the whole plot. Because it is just a tale snippet, there’s no strangeness with a young character (four year old DW) playing Snow White, who is generally at least a teenager.

The reason that fairy tales stick around and are constantly adapted is that they are loose and open about details. Coincidentally, this causes the difficulty with this project, which set out to draw conclusion based on assumptions about categorizing tales according to their details. Children’s television mash-ups, I think more than any other kind of television, really stretch and manipulate fairy tales to their limits. The narrative gymnastics required to mix together different fairy tales, as well as to fit the fairy tales into the established premise of the show, takes creativity and innovation. No two products of this process end up alike, which is why this project was such a frustrating, complicated, and delightful experience.